“We need to bring Android and Chrome to every screen that matters for users.” That was Google CEO Sundar Pichai speaking at Google I/O 2014. Seven years later and Pichai’s vision may finally be coming to fruition but perhaps not in the way he’d envisioned.

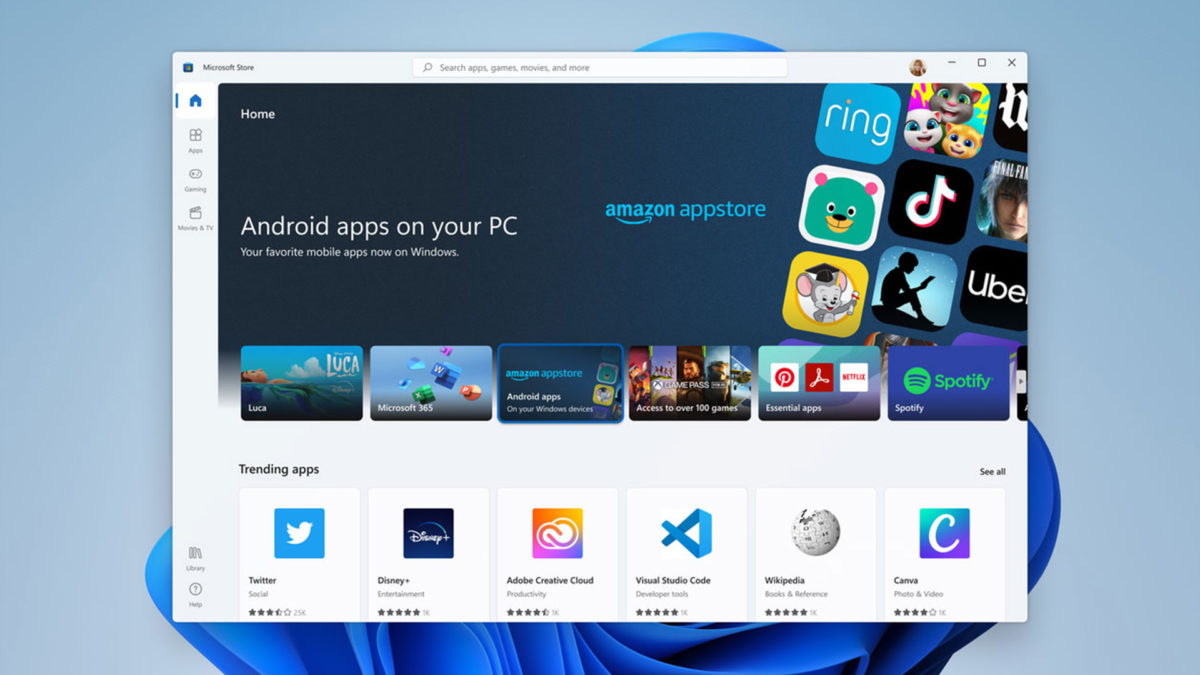

It’s taken the combined forces of Amazon and Microsoft to bring the core of the Android experience — the all-important apps — to millions more users with the introduction of native Android app support on Windows 11. The solution is a potential game-changer for the way users will interact with their favorite apps, smartphones, and PCs, but it’s perplexing that the initiative hasn’t been driven by Google but by one of its biggest rivals.

Google has always talked strongly about the merits of open-source software at the heart of Android and the benefits of open platforms to drive innovation and bring technology to the masses. To quote Pichai once more, “when you run a platform on scale, you have to make sure it’s truly open. That way, not only do you do well, so do others.”

That’s certainly true. Google’s smartphone, smart home, and TV products wouldn’t be the successful, cross-hardware ecosystems they are today without expansive partnerships and mutually beneficial collaboration. The recent Google and Samsung partnership for Wear OS 3.0 is just such an example. Considering Google has shown time and time again that it can’t be trusted to properly integrate its behemoth service portfolio across even its own hardware, it’s good that the search giant is ostensibly so open to playing nice with others.

However, the company’s actions over the past decade have often failed to live up to this ethos. On the one hand, Google preaches openness and competition yet retains an iron grip on its software with the other. This is particularly true when it comes to Android and its biggest tech rivals.

See also: Why did Microsoft choose Amazon over Google for Windows 11 Android support?

You don’t have to look far to find examples of Google’s uncooperative approach to rival ecosystems. Near the start of the last decade, Google infamously blocked Microsoft’s YouTube app for the latter’s ill-fated Windows Phones. For more recent examples, Google reportedly forbids Android TV partners from engaging with other Android forks (see: Amazon Fire TV). The Mountain View firm also dragged its heels updating its apps to meet Apple’s new App Store privacy labels.

The most controversial and powerful tool with which Google asserts control over Android and its associated app ecosystem is Google Mobile Services (GMS). GMS is a set of programming features (APIs) for developers to tap into Android’s tools for location data, payments, security, and other very common features used by closed-source Google apps and third-party software.

Android may be open-source, but you have to play by Google’s rule if you want access to the ecosystem’s biggest app store.

However, GMS licenses are only granted to devices that comply with Google’s Compatibility Definition Document (CDD) and associated tests. This means you have to support all of Google’s services, such as ads and the store, even if you just want to just use Google’s location API. Even then, obtaining a license has strict conditions. 2013’s Play Store licensing agreement demanded that companies not take any actions that would cause “fragmentation of Android.” Such as developing a forked-OS. Competition is fine but only when it benefits Google.

Demands like this have been deemed unfair in the EU, resulting in a hefty $5 billion fine in 2018. The ruling saw the company eventually change its EU requirements for Google services on Android in 2018. Of course, that didn’t change the status quo in other markets including, most notably, the US.

The Big G markets GMS and its Play Services as tools for ensuring high-quality, consistent user experiences across apps and hardware. That’s true, to some extent. However, it’s also a stick with which to prod and punish manufacturers that dare take Android in its own direction. And remember, Google ultimately decides and maintains what goes into the main Android open-source project.

While Android remains free for anyone to use as they would like, only Android compatible devices benefit from the full Android ecosystem.

Importantly, without GMS, your device can’t run Google’s own apps or other apps that rely on associated services and APIs. The loss of the Google Play Store is undoubtedly the biggest potential loss, but there are other features, such as locations for Uber, or WhatsApp’s Drive backup feature, that rely on GMS for core functionality. This is the reason that Amazon and Huawei — the latter of which has seen its smartphone empire crumble outside of China without access to GMS — both have their own app stores and a more limited selection of software on their forked versions of Android OS. And yes, this also means that Windows 11 won’t offer all the apps you’re probably used to using inside Google’s ecosystem.

So why is all that important? For starters, it shows how Google controls the developer tools, distribution platforms, and even the hardware that falls under its ecosystem. It’s a self-enforcing power structure that Google won’t easily part with, especially for a rival like Microsoft.

The result is a contradictory approach to open collaboration. The company has long touted the benefits of open software and standards, yet staunchly opposes competition at the edges of its ecosystem. Google could compromise and make GMS more readily accessible to bring its entire library of apps to Windows and other ecosystems, but it has chosen not to. Just like how it brought the Play Store to Chrome OS but not to Linux more widely.

The irony is that Google had the right message for years but its actual approach is becoming increasingly flawed. Consumers are more likely to embrace platforms that enable them to run the same software across multiple devices. Ideally, I want to run exactly the same messaging, fitness tracking, and banking apps with identical features across all my gadgets. Amazon’s Android app support on Windows is a major step towards this reality. Likewise, there’s a similar direction of travel over at Apple, which is quickly aiming for app and hardware parity across iOS, iPad, and Macs.

Google’s contradictory approach to open collaboration is preventing it from bringing apps and services to millions more devices and users.

Google faces losing out on multi-platform momentum while its biggest rivals benefit. Amazon stands to profit from app sales and much greater exposure on Microsoft’s platform. I wouldn’t be surprised if Amazon’s Fire TV, tablet, and smart home products see a boost to sales too. Meanwhile, Windows 11 benefits from a whole host of new cross-platform applications and it represents another step outside the venerable OS’ traditional PC-only base.

Panos Panay, Chief Product Officer for Windows, recently stated that all stores and apps are welcome on Windows, hinting that the company remains open to working with Google. But unless Amazon’s move really shakes things up, it seems doubtful that Google will want to loosen the grip on its Android app ecosystem and give us the vision of computing it has been talking about for so long.